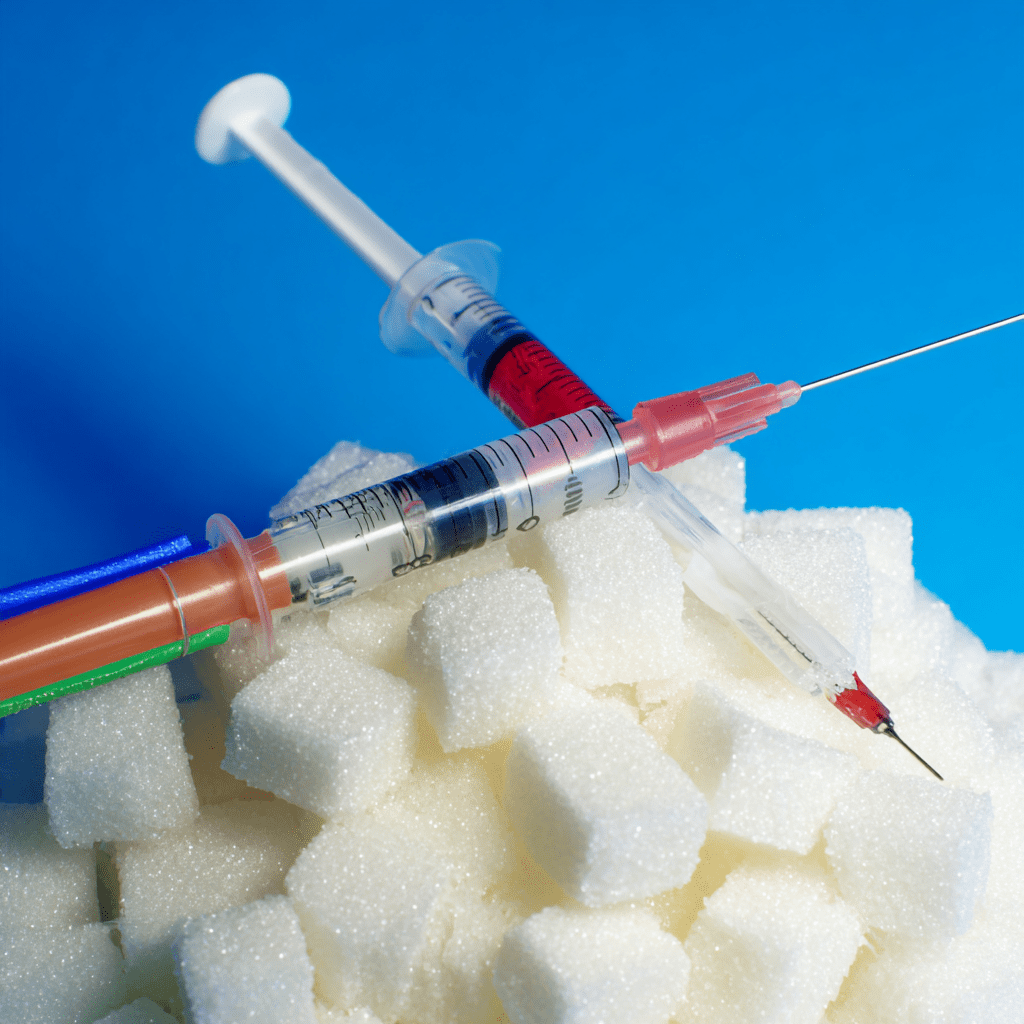

In the modern diet, sugar and refined carbohydrates are ubiquitous, driving sharp, frequent spikes in blood glucose that strain the pancreas, promote insulin resistance, and inflict systemic damage on blood vessels. While the simple solution is often presented as rigorous avoidance, the reality of a modern lifestyle makes complete elimination difficult. A more practical and powerful strategy lies in harnessing the natural defense mechanism provided by fiber, particularly the sticky, water-soluble kind.

This is the concept of the “Fiber Shield” effect: a protective mechanism where soluble fiber, consumed alongside or shortly before carbohydrates, forms a physical barrier within the digestive tract. This barrier slows the absorption of sugars into the bloodstream, effectively dampening the post-meal glucose surge. This simple physiological action is a critical tool for maintaining metabolic resilience, protecting against the long-term harms of sugar, and stabilizing energy throughout the day.

The Source of Metabolic Stress

To appreciate the protective action of fiber, one must first understand the mechanism of sugar damage. When a refined carbohydrate (like white bread, juice, or a sugary snack) is consumed, it is quickly broken down into glucose.

1. Rapid Absorption and the Insulin Overload

- High Glycemic Index: Refined carbohydrates have a high glycemic index, meaning they cause glucose to flood the small intestine rapidly.

- Aggressive Spike: The rapid influx of glucose leads to a sharp, high peak in blood sugar (hyperglycemia).

- Insulin Rush: The pancreas is forced to release a massive, immediate surge of insulin to bring the glucose down. This repeated, aggressive demand on the insulin system over time leads to cellular exhaustion and the progressive decline of insulin sensitivity.

2. The Cycle of Damage

Chronic high blood sugar and repeated insulin surges are corrosive. They contribute to:

- Vascular Damage: Glucose molecules bind to proteins in a process called glycation, leading to the formation of Advanced Glycation End products. They accelerate damage and stiffness in blood vessel walls, setting the stage for heart disease and microvascular issues.

- Fat Storage: High insulin levels signal the body to stop burning fat and instead aggressively shuttle all available energy, including any excess glucose, into storage, often in the form of visceral fat and liver fat (steatosis).

- Energy Crash: The rapid insulin spike often overshoots, leading to a quick drop in blood sugar (hypoglycemia) 1-2 hours later, resulting in fatigue, brain fog, and intense cravings for more sugar, perpetuating the unhealthy cycle.

The Mechanism of the “Fiber Shield”

Soluble fiber, found in foods like oats, beans, legumes, apples, and psyllium husk, is the defense mechanism against this metabolic chaos. When soluble fiber mixes with water in the stomach and small intestine, it creates a unique, highly viscous, gel-like matrix.

1. Viscosity and Physical Barrier

The increased viscosity of the stomach contents has several effects that constitute the “shield”:

- Slowing Gastric Emptying: The gel physically slows the rate at which food leaves the stomach and enters the small intestine. This deceleration is critical because it prevents the large, immediate dump of glucose that causes the initial high spike.

- Creating a Diffusion Barrier: Once in the small intestine, the fiber gel creates a physical barrier along the intestinal lining. Glucose molecules from the meal must now diffuse (slowly pass) through this thick, sticky matrix before they can reach the absorptive cells. This dramatically slows the rate of glucose absorption into the bloodstream.

2. Flattening the Glucose Curve

The result of this physical shield is a profound alteration of the post-meal metabolic response:

- Lower Peak: The blood glucose curve is flattened. The peak blood sugar level is significantly lower than it would be without the fiber.

- Sustained Release: Instead of a sharp, damaging spike, the glucose is released slowly and steadily over a period of hours.

- Reduced Insulin Demand: Because the body is only dealing with a moderate, continuous stream of glucose, the pancreas only needs to release a moderate, sustained dose of insulin, preventing the overwhelming insulin rush and subsequent crash.

This regulated, efficient delivery of nutrients reduces the metabolic strain, lowers AGE formation, and helps preserve long-term insulin sensitivity.

Indirect Metabolic Benefits

The benefits of the Fiber Shield extend past mere physical blockage, offering secondary metabolic advantages that further protect the body from sugar-related harm.

1. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) and Hepatic Glucose Control

Once soluble fiber reaches the large intestine, it becomes food for the beneficial gut bacteria (the microbiome) through a process called fermentation. This process generates powerful byproducts known as Short-Chain Fatty Acids, primarily butyrate, acetate, and propionate.

- Liver Signaling: SCFAs travel to the liver where they play a direct role in signaling. Specifically, they help suppress excess hepatic glucose output, the liver’s release of stored glucose. In conditions like insulin resistance, the liver inappropriately dumps glucose into the blood even when a person has just eaten. SCFAs help regulate this process, offering another layer of defense against high blood sugar.

2. Improved Satiety and Reduced Overconsumption

The viscosity of soluble fiber increases feelings of satiety (fullness) in two ways:

- Stomach Distention: The expanded, gel-like fiber takes up more physical space in the stomach, promoting feelings of distention that signal fullness to the brain.

- Hormonal Signals: The fermentation process, and the presence of SCFAs, stimulates the release of key satiety hormones like GLP-1 and PYY from the gut cells.

By increasing fullness, the Fiber Shield indirectly prevents the overconsumption of carbohydrates and simple sugars at subsequent meals, helping to maintain a lower daily glycemic load and reducing the overall volume of sugar the body must process.

Implementing the Fiber Shield Strategy

The Fiber Shield effect is not passive; it requires intentional timing and selection of fiber sources.

1. Fiber Timing is Key (The Pre-Load)

For maximum shielding benefit, soluble fiber must be present in the digestive tract before or with the most highly refined carbohydrates.

- The Fiber “Appetizer”: Consume a small serving of soluble fiber such as a salad, a handful of nuts, or a small bowl of oats 10-15 minutes before consuming a meal that includes simple starches or sugars. This gives the fiber time to swell and form the protective gel before the glucose flood arrives.

- Inclusion: Always include whole food sources of fiber within the meal itself, such as pairing rice with beans, or fruit with its skin.

2. Focus on Soluble Sources

While all fiber is beneficial, the “shield” effect relies specifically on highly viscous soluble fiber. Excellent sources include:

- Legumes: Beans, lentils, chickpeas (extremely high in both soluble and insoluble fiber).

- Oats: Especially rolled or steel-cut oats (beta-glucans).

- Certain Fruits and Vegetables: Apples, citrus fruits, Brussels sprouts, asparagus.

- Supplements: Psyllium husk, glucomannan, or guar gum are highly effective for creating viscosity.

Conclusion

The modern metabolic challenge is often characterized by hyper-reactivity to the sugars in our diet. The Fiber Shield effect offers a powerful, natural solution by reintroducing a crucial evolutionary defense mechanism. By using soluble fiber to physically slow down the absorption of glucose, we reduce the aggressive metabolic shock of the sugar spike, dampen the harmful insulin response, and leverage the beneficial signaling from SCFAs. Embracing this strategy is not just about managing sugar; it is about restoring metabolic stability, preserving the health of our blood vessels, and promoting a more energized, resilient biological system.