If you can press on your chest and make the pain worse, there is a good chance the source is the chest wall—often costochondritis, an inflammation where the ribs meet the breastbone. But pressing pain does not automatically mean you are safe from heart trouble, and squeezing, pressure-type discomfort can come from both the heart and the chest wall. The safest approach is to learn the key differences, know the red flags, and understand how clinicians separate harmless chest wall pain from a heart attack or other time-critical causes. The guidance below is evidence-based and reflects modern chest-pain evaluation standards. [1]

Immediate safety note: If chest pain lasts more than a few minutes, recurs, or is accompanied by shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, fainting, or pain spreading to the arm, jaw, back, or upper stomach—call emergency services now. Do not drive yourself. These are classic warning signs of a heart attack. [2]

What Costochondritis Actually Is (and How It Feels)

Costochondritis is an inflammatory irritation of the cartilage where ribs meet the sternum (costochondral or chondrosternal joints). The pain is usually sharp or aching, well localized, and reproducible when you press along the rib–breastbone junctions or when you move, twist, cough, or take a deep breath. It often affects several adjacent joints and does not cause visible swelling. A related condition, Tietze syndrome, looks similar but typically involves swelling at a single rib–sternum joint (classically an upper rib). Both are chest-wall causes of pain and are benign—but they can mimic heart trouble. [4][6]

Typical triggers include a recent upper respiratory infection with coughing, a new exercise or lifting routine, awkward posture or prolonged computer work, or minor trauma. In many people, costochondritis improves on its own over weeks to months with simple measures like rest, heat or ice, and anti-inflammatory medicines—though persistent or severe cases may need targeted physical therapy or, rarely, a local corticosteroid injection.

What Heart Trouble Means In This Context

When clinicians worry about chest pain from the heart, they are thinking about acute coronary syndromes (heart attack and unstable angina) and other emergent causes such as aortic dissection, pulmonary embolism, and pericarditis. The 2021 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association chest-pain guideline emphasizes that chest pain descriptions vary, women and older adults can have atypical symptoms, and rapid risk-based testing is crucial. [1]

Classic Heart-Related Features to Take Seriously Include:

- Pressure, tightness, or squeezing in the center or left chest, sometimes described as “an elephant on my chest.”

- Pain that spreads to the arm (one or both), shoulder, neck, jaw, back, or upper stomach.

- Symptoms brought on by exertion or emotional stress and relieved by rest.

- Associated shortness of breath, nausea, sweating, lightheadedness, or fainting. [2]

Again: if these appear, treat it as an emergency. [2]

The Press Test: Helpful—But Not a Guarantee

Many people notice that costochondritis pain is tender to touch. That clue helps—several studies show that reproducible chest wall tenderness makes a heart attack less likely, particularly in low-risk settings. But the same research and guidelines are clear: tenderness does not rule out a cardiac cause. Chest pain evaluation should not stop at the press test when the history or risk profile is concerning. [3]

Think of tenderness as a probability shifter, not a diagnosis. If you have risk factors (age, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, family history), if the pain is pressure-like, if it comes with shortness of breath or nausea, or if you are simply uncertain—get checked.

How Doctors Tell The Difference in Real Life

Modern chest-pain care follows a structured pathway:

History and targeted examination

Clinicians map the pain location, quality, triggers, and associated symptoms; they palpate along the costochondral joints for reproducible tenderness and look for swelling (suggesting Tietze syndrome). They also assess pulse, blood pressure in both arms, oxygen level, and lung and heart sounds.

Electrocardiogram and high-sensitivity troponin blood tests

These are the core tests to rule out a heart attack or unstable angina. The 2021 cardiology guideline recommends early electrocardiogram and serial high-sensitivity troponin when indicated, using clinical-risk tools to guide timing and disposition. [1]

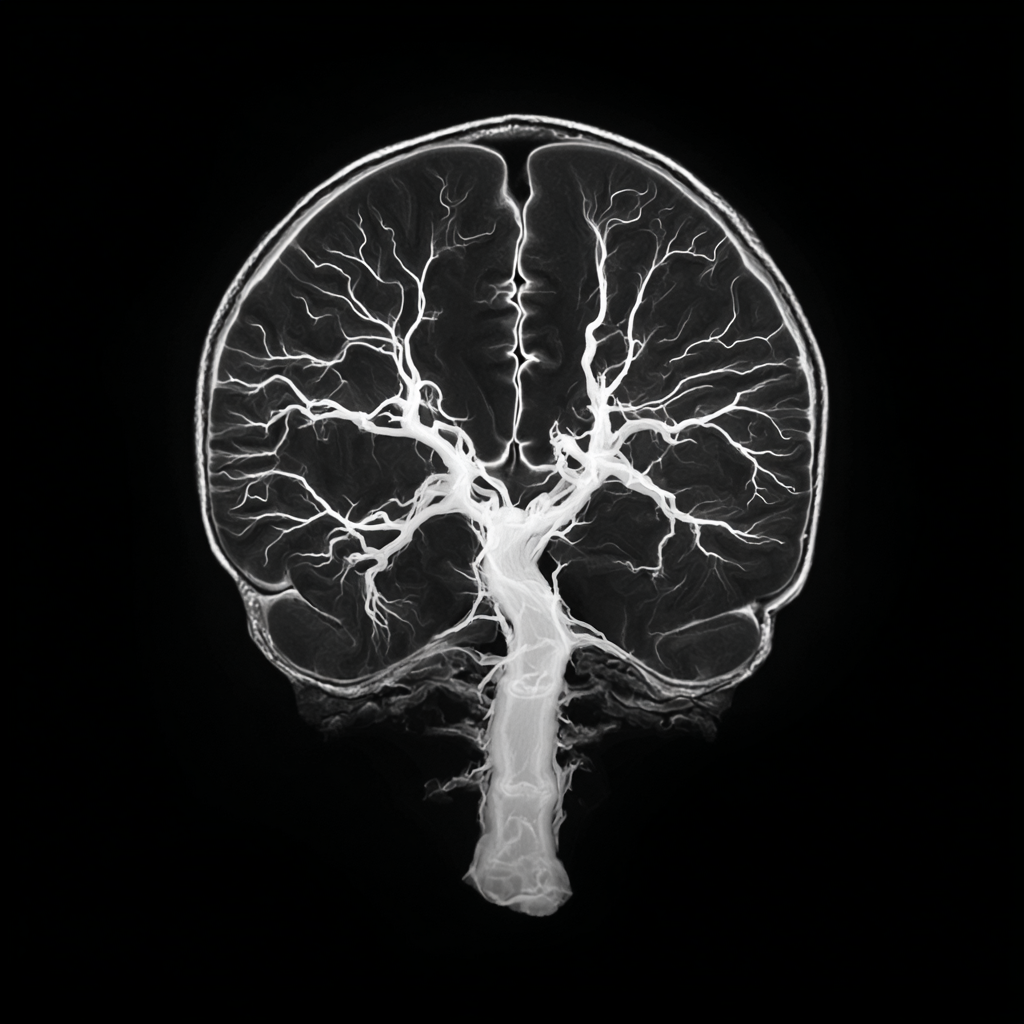

Imaging as needed

If the story fits chest wall pain and the cardiac workup is negative, most people do not need advanced imaging. If heart disease remains possible, the team may consider coronary computed tomography angiography or stress testing based on risk. If lung or clot causes are suspected, they may order chest radiography or a computed tomographic scan of the lungs. [1]

Diagnosis of costochondritis is clinical

There is no single laboratory or imaging test for costochondritis. It is diagnosed when the history and exam fit, other dangerous causes are excluded, and palpation reliably reproduces the pain. [4]

How costochondritis and heart-related pain typically differ

Below are pattern differences (no single sign is perfect):

Location and touch

Costochondritis pain is point-specific near the rib–sternum junctions and worsens when you press there; heart-related discomfort is often diffuse, deep, or pressure-like and not clearly tender to touch. [4]

Movement and breathing

Costochondritis worsens with twisting, lifting, certain sleep positions, deep breathing, or coughing; heart-related pain often worsens with exertion and improves with rest.

Radiation

Cardiac pain may spread to the arm, jaw, or back; costochondritis is usually local (though it can radiate along the chest wall). [2]

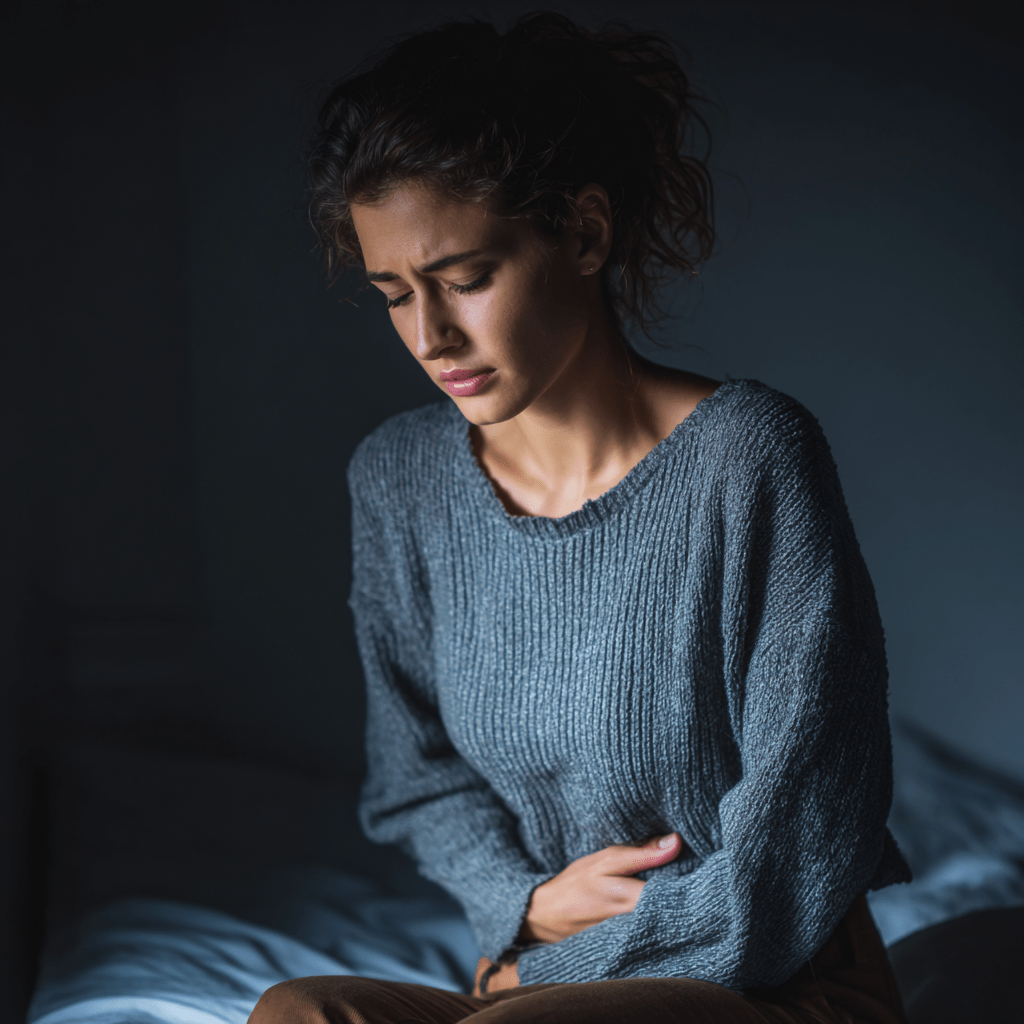

Associated symptoms

Costochondritis usually lacks shortness of breath, nausea, or sweating; those symptoms raise concern for heart or lung causes. [2]

Swelling

Tietze syndrome—a cousin of costochondritis—can show visible or palpable swelling at a single joint; classic costochondritis does not. [5]

These patterns guide urgency, but they never replace medical evaluation when red flags are present.

When to go to the emergency department right now

- Chest pressure, tightness, or pain lasting more than a few minutes, or that comes and goes.

- Pain spreading to the arm, jaw, neck, back, or upper stomach.

- Shortness of breath, sweating, nausea, dizziness, or fainting.

- New chest pain in someone with heart-disease risk factors (age, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, family history).

- Chest pain that started with exertion or stress. [2]

Call emergency services; early treatment saves heart muscle and lives. [2]

Proven treatments for costochondritis (and what to expect)

Most cases improve with conservative measures:

- Relative rest and activity modification for a short period.

- Heat or ice to the tender areas based on comfort.

- Anti-inflammatory medicines (topical or oral) if appropriate for you; discuss stomach, kidney, or bleeding risks with your clinician.

- Gentle mobility and posture work: breathing drills, thoracic mobility, and pectoral/shoulder-girdle stretches reduce joint stress as pain settles.

- Targeted physical therapy if symptoms linger.

- Local anesthetic and corticosteroid injection only for persistent, clearly localized pain after evaluation—used sparingly. [4]

Timeline: Many people improve over weeks; some need months. A minority experience recurrences, often after coughing illnesses or heavy upper-body strain. If your pattern is not improving as expected, see your clinician to re-check the diagnosis.

What about Tietze syndrome?

Tietze syndrome is an uncommon chest-wall condition with pain and swelling at a single costochondral junction (often the second or third rib). Management is similar to costochondritis—rest, pain control, and time—though the visible swelling can persist for a while. Persistent or unclear swelling deserves medical review to exclude other causes. [5]

Frequently asked questions

If pressing makes the pain worse, is it definitely not my heart?

No. Reproducible chest wall tenderness makes a heart attack less likely, especially in low-risk patients—but it does not absolutely exclude a cardiac cause. If in doubt, seek care. [3]

Can stress or anxiety cause chest pain that feels like costochondritis?

Yes—anxiety can amplify muscle tension and pain perception, and panic can mimic heart trouble. Still, new chest pain deserves a proper evaluation to rule out dangerous causes. The chest-pain guideline emphasizes not attributing symptoms to anxiety before appropriate testing.

Do I need an X-ray or scan for costochondritis?

Usually no. Costochondritis is a clinical diagnosis; imaging is reserved for alternative concerns (fracture, lung disease) or atypical features.

How do doctors decide whether to run heart tests?

They combine the story, exam, electrocardiogram, and high-sensitivity troponin, then use risk-based pathways from the 2021 cardiology guideline to decide observation, discharge, or additional testing. [1]

Is there anything I can do at home while I wait for an appointment?

If you are certain there are no red flags, you can try brief rest, heat or ice, gentle posture resets, and over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medicine if safe for you. But if symptoms persist or you are unsure—get evaluated. [6]

A clinician’s mental checklist (what your doctor is thinking)

Is this time-critical heart disease? First priority is to rule out heart attack or unstable angina with history, exam, electrocardiogram, and high-sensitivity troponin. Delay kills muscle. [1]

Does the chest wall reproduce the pain? Point tenderness at the rib–sternum junctions strongly suggests costochondritis but does not end the workup if risk is elevated. [3]

Any red-flag patterns? Exertional pressure, radiation, shortness of breath, syncope, or risk factors → treat as cardiac until proved otherwise. [2]

If costochondritis fits, can we spare imaging and focus on relief and function? Most cases respond to time, activity adjustment, and anti-inflammatory strategies; physical therapy for stubborn cases; injections rarely. [4]

Practical self-care plan for costochondritis (once dangerous causes are excluded)

Unload the joints for 1–2 weeks. Scale back heavy presses, dips, rowing, or repetitive overhead work. Use a lumbar roll and adjust chair height to avoid rounded shoulders.

Breathing and mobility, daily: gentle rib-expansion breathing, thoracic extension over a towel roll, and pectoral doorway stretches—short and frequent sessions.

Heat before movement, ice after activity if either improves your symptoms.

Topical anti-inflammatory gel on the tender rib–sternum area if safe; discuss oral anti-inflammatories with your clinician.

Gradual reload: reintroduce pushing and pulling with light resistance first; stop short of sharp reproduction of pain and progress every few days as tolerated.

If pain persists beyond a few weeks, worsens, or changes character—recheck with your clinician to revisit the diagnosis and options. [6]

The Bottom Line

Costochondritis is a common, benign cause of chest wall pain that is tender to touch and often flares with movement or deep breathing. It usually improves with time and simple measures. [4]

Heart trouble can present with pressure-type chest discomfort, radiation to the arm or jaw, shortness of breath, nausea, sweating, or fainting—and it remains possible even when the chest wall is tender. If you are unsure, act fast. [2]

Clinicians follow risk-based pathways using electrocardiogram and high-sensitivity troponin to quickly rule in or rule out a heart attack. You should not self-diagnose or delay care when warning signs are present. [1]

With the right mix of caution and knowledge, you can respect chest pain without fearing every twinge. Treat press-to-tender pain like costochondritis once the dangerous causes have been excluded—and never ignore symptoms that fit heart trouble.

References:

- 2021 ACC/AHA chest-pain guideline: risk-based evaluation, electrocardiogram and high-sensitivity troponin strategy, and testing pathways. AHA Journals

- American Heart Association: classic heart-attack warning signs and “call now” guidance. heart.org

- Reproducible chest wall tenderness and the likelihood of acute coronary syndrome: evidence from primary care and emergency settings. PMC

- Costochondritis diagnosis and management: rapid evidence review and primary-care guidance. PubMed

- Tietze syndrome vs. costochondritis: distinguishing feature is swelling at a single joint. Cleveland Clinic

- Self-limited course and conservative care for costochondritis: national health guidance. nhs.uk